|

Vance

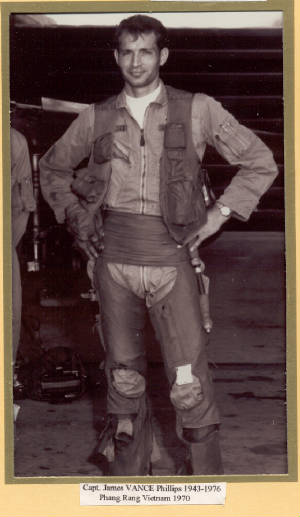

Phillips, A Fighter Pilot

Vance Phillip’s younger brother

Dee told me this story first in 1990 at a high school reunion in Odessa, Texas, where I just accidentally ran across him. Some of the other information came to me via Vance’s wife Nancy Hinds Phillips

when she moved to Round Rock, Texas in the late seventies. When Dee told

me the story I remember wondering if Dee might have been slightly embarrassed in the telling of the story to me, but I have

recently talked to Dee by phone to make sure of the accuracy of some of my facts and he has reassured me that he fully understood

the environment in which this story took place, and like me and numerous Air force pilots to whom I have related this event,

was more than a bit amused by it all. In fact, Dee said even his mother got a

kick out of it.

In a letter to me, Dee said he was “glad

that Vance did what he did.” This shows the sense of humor in the Phillips

family because Dee has a son in the Navy in this year, 2003, and that son is flying F-18 Hornet Fighters off of a carrier,

so Brother Dee is more than aware of the factors that existed during the times and situation that existed years ago.

Before I get into the incident itself,

and just for the sake of veracity and history, I need to state that I followed Vance’s career the best I could because

he was a friend and secondly because I am an aviation freak and I have been since the mid-60s when I became a civilian flight

instructor training USAF pilots in the Air Force T-41 program.

The

T-41 program was a primary flight school funded by the USAF for the purpose of teaching new Air Force student pilots how to

fly. The aircraft used in this T-41 program was a military version of the Cessna 172. Of course, all the students were

military and all of us instructors were civilians employed by contract and supervised by military officers. The program was designed to shave the cost of flight training for new pilots by identifying those potential

pilots who would or could not hack the program. The guys who had no aptitude for flying were washed out in a relatively

inexpensive to operate airplane rather than in the jets that were used before Viet Nam heated up into a full-blown war. Vance went through this program as the first phase of his military flying, and even

though he was not stationed where I was an instructor, we were both aware of each other’s activity at the time, so much

for the veracity.

As far as the history goes, Vance and

I lived on the same block of Windsor Drive within a few doors of each other in Odessa, Texas in the 50’s, and early

60’s. His best friend at that time was also a pal of mine, Johnny Ben Sheppard,

who lived just across the street from me. The three of us together would often

dream up mischief at night together in our old neighborhood. The specifics of

those adventures are best left untold, but we were in our mid-teens and mischief came easy with us.

After graduation from high school and

after we all went our separate ways, and as the years passed, I would occasionally call Vance’s parents, Ed and Trigger,

to keep track of Vance. I know he entered the Air Force in 1967 just after I started my aviation career as a flight

instructor in the aforementioned USAF T-41 program. In 1967 Vance and I once

talked by phone in Odessa over a Christmas holiday season right before he was to report to pilot training in Alabama early

in the year of 1968. After that conversation, many years went by without any

contact between us until around early 1976. In that year I wrote to him by addressing

the letter to his parents’ home in Odessa, knowing they would forward it to him.

I wrote him and his wife Nancy Hinds a letter asking to be updated on his career.

I got back a very warm letter from the two of them. I remember that letter

vividly even though I can no longer find it.

At the time of the update, Vance and

his wife Nancy were stationed at Nellis Air Force Base outside Las Vegas, Nevada. It was then that I began learning

just how spectacular his Air Force career must have been. Vance had become a flight instructor in the Aggressor Squadron.

It was said at the time that the Aggressor Squadron flight instructor job was the best job to be had in the Air Force in that

era because it was a squadron designed to simulate air combat conditions that would be encountered with the best of the Russian

pilots flying the best of the Russian fighter aircraft. The Aggressor squadron was similar to the Navy’s Top Gun

school and it was in addition to The Red Flag program the USAF had put together for Air combat training earlier on for the

Viet Nam War.

Those guys in the aggressor squadron

got to do what any fighter pilot loves to do, dogfight all day in fast jet airplanes.

Any fighter pilot of that era would have given all he had or could ever hope to have for that job because they flew

against the best we had and they flew the hottest airplanes we had. It was a dream job.

You can be the United States Air Force offered that job to the best pilots they had.

Vance Phillips evidently was among the best in the Air Force at that time.

I

do know that he had to graduate very high in his class to get the assignment that he got after finishing flight training. He got an F-100 fighter assignment and at the time that assignment was rare because

other types of airplanes were starting to replace that favorite. It is said that

the F-100 was the last fighter that was strapped onto the pilot. In other words

it was a pure fighter and it was not asked to do so many other things that the next generation of fighters were being asked

to do. Fighter pilots loved it. In

those days it was the vision of Defense Secretary Robert McNamara, the fool, that the military should have an all around airplane

that could do a multitude of jobs. This was not a good idea and it did not work. But in the mean time there was a war in Southeast Asia that was being fought and Vance

found him self right in the thick of things flying his choice of airplanes, the F-100 Super Sabre.

After his tour in Viet Nam, and while

in the Aggressor Squadron assignment, Vance was killed in early May of 1976 on a training mission in a T-38 jet trainer eighty

miles off the coast of Virginia when his ejection seat malfunctioned by arming itself and firing without warning to Vance.

It was a freak accident. Neither Vance nor his aircraft was recovered.

The student flying with him survived. The news of that accident was broadcast nationwide. I’ll never forget the

sickening feeling when I heard the story.

There was another time when Vance made

the news nationwide in his career while flying an F-100 Super Saber fighter over Cambodia in some of the hottest action of

the war. Vance’s airplane was hopelessly damaged by enemy fire, but he managed to eject over water and was successfully

rescued. I know the Cambodia story because I was zooming across the remote plains of Wyoming driving back to Denver in the

late 60's listening to the car radio when the news came on telling about Air Force Lieutenant Vance Phillips from Odessa,

Texas, surviving that experience. It was a strange feeling to hear that news, in that time, in that place, of a friend

of mine from our home town.

Some months later while on another mission in Viet Nam he again had to eject because his

airplane had just been shot up so badly that he could not have landed it. The

second incident resulted in his receiving the Distinguished Flying Cross. I have the feeling Vance hung on in tough situations

when few others would. It is no secret that some pilots in that war had to be

urged to fly some of the crazy and too dangerous combat missions that Defense Secretary McNamara dreamed up on his own in

those days. I’ll bet that Vance Phillips did the job he was asked to do

and more. That was his style

Dee Phillips’ story to me is one

story that will never be told in the news, but it is a story that I can say typified the Vance we all knew growing up.

Keep in mind, Vance lived at full throttle, the same way he flew fighters, all out. He flew the Air Force’s fighters

“like he was trying to tear them up.” I heard that statement from Vance’s Uncle Chuck Phillips of

Austin, Texas, where Chuck and I became friends in the early 70’s. Uncle

Chuck was a bomber pilot in World War II. Chuck and Vance’s dad were brothers; both of them were very fine men.

Over the years in the early to mid seventies I kept up on the news of Vance’s career through Chuck in Austin, Texas

right up to the time of Vance’s death in May 1976.

To fully

understand the following incident and to keep it all in the proper perspective it needs to be well understood by any reader

that the rivalry between our Navy and Air Force Pilots is more intense than any rivalry such as the rivalry between schools

like the University of Texas and Texas A&M or Notre Dame and Southern Cal, or Arizona State and University of Arizona

or Ohio State and Michigan. Put all of them together and multiply them by a factor

of your choice. It is fierce rivalry. Also,

it is important to remember that the hottest aircraft in the USA are often flown by fuzzy face kids fresh from our colleges,

and those fuzzy face kids who eventually are chosen to fly fighters are always at the top of their class out of pilot

training. They are at the top of their class because they fit a profile of being

the most competitive and self-demanding of all the guys in the program. It is a hot mixture of factors and knowing that, please

realize anything can happen with these guys. It is a man show with fighter airplanes.

Plus, consider that the Navy pilots boast

they are the best pilots in the world because they are able to conduct their combat missions while performing the most difficult

flying task in the world: flying off the deck of an aircraft carrier at night and in bad weather when the ship is pitching,

rolling and faced into high gusty winds and bad seas while churning along at nearly 30 knots.

It is a tough job and the Air Force knows it.

Also, at the heart of the rivalry is

the Navy's perceived arrogance and pomposity toward their fellow brethren in the blue suits whom are seen by those Navy pilots

as just incapable of doing the job the Navy has to do.

Of course the blue suiters in the Air

Force say that any of them could do the job if they were given the same training. So goes the bantering and debating

between these highly competitive souls. The rivalry is made even the more bitter over the media’s presentation of the

two services, with both services pouting that their respective service gets less favorable publicity than the other. The most famous pilot of all history is probably the Air Force’s Chuck Yeager,

who broke the sound barrier in 1948, and has mountains of pages written about his exploits.

His notoriety alone accounts for a great deal of the acrimony between the two services, and to the uninitiated, the

movie industry’s movie, TOP GUN made Navy flying legendary to the latest generations.

It was too cheesy for me, but I loved the music!

Dee Phillips story began by his telling

me that in 1974 at age 31 Vance got accepted into an exchange program between the Air Force and the Navy in which he would

go aboard a Navy carrier, and a Navy carrier pilot would likewise go through the Air Force combat mission training.

It was an honor for Vance to be picked by the Air Force and to be handed over to the Navy for a Navy tour at sea. The

Air Force wanted to send one of their best and most competitive pilots to the Navy. They picked Captain Vance Phillips

of Odessa, Texas. It was a good choice.

Events like this are not news items we civilians would ever hear about,

but

the fighter pilots on each side of that infamous rivalry know how it all

worked.

One way that it all works is that the

Navy jocks are in constant competition with one another when it comes to the best execution of landings on the carrier deck.

There is a fierce scrutiny of each approach and landing; each exercise is graded, and the flight crews throughout the tour

monitor their grades. The leader with the highest score is like a rhinestone cowboy with honors and recognition and

probably a lot of ribbing along the way. Frankly, for an Air Force guy to lead that competition on their carriers is,

well, a painful slap in the face to those who love to dig at the "inferior" flying the USAF does compared to the “superior”

flying of the pilots of the Navy. The rivalry is fierce.

Let the record show Vance Phillips, the

Air Force pilot, won that competition during his tour at sea with the Navy.

So, upon his departure of the carrier

at tour's end, there was a farewell ceremony honoring him as the hottest jock aboard. These ceremonies are the climatic event

of a lot of stress and then relief from getting back home alive and it is a little more than likely that a bit of alcohol

is consumed during said meetings. Navy gatherings can be infamous. Tail-hookishly infamous.

Vance was a guest of honor at this gathering of his peers and they all

were celebrating his accomplishments while sending him back to the Air Force. There

were high-ranking officers and their wives in attendance and Admirals and other officers in bright white uniforms. Vance was introduced and went to the podium where he was given his award, and where he was expected to

say a few words.

After saying a few words Vance the honoree

said something to the effect, “ Now here is what I think of you Navy pukes.”

He then turned around, bent over and mooned the Navy.

Brother Dee, in his letter to me further

states, “It is unclear to this writer whether this was done linen up, or linen down, but it is definitely the thought

that counts.” Dee further stated in effect that even though Vance always

was for a good time he doubted Vance would have totally insulted the Admiral’s wife.

Case closed. Linen up.

There was no doubt raucous laughter and

returned gestures of some type. Vance then left the stage.

Dee assures me that the family understood

the circumstances, so I don’t know for sure if there might be some who knew Vance who wished that he had not done what

he did. It is a reasonable guess that some of them might have wished he had accepted the honors in a humble and grateful

fashion, in a way that would have allowed them to write home to the local newspaper of his accomplishments. But, that was not the way of one of the Air Force’s most competitive pilots. I can dang sure guarantee

that the entire USAF who became aware of what he did in his farewell address to the Navy, got the laugh of their life, and

they loved Vance for doing what he did.

The pilots who were his friends in the

Air Force and who knew Vance Phillips understood that he did what he did for his pals who endured the insufferable taunting

of those who fly off carriers and say, "I can do it and you cannot do it."

Should anyone in our civilian world think that this was ungentlemanly and crude,

I also would like to point out that it did not diminish the respect the Navy pilots had for Vance. In that world, it was nothing to them except a hearty laugh given to them by someone as competitive as

they were and they respected him for his abilities and Úlan.

Friendships were made on that cruise

that outlasted the farewell. In fact, some years after Vance’s death, an

old Navy buddy looked up Vance’s widow, Nancy Hinds Phillips, and married her.

I’d like to think that Vance, being the man that he was, would have wanted the best for his wife and kids he

left behind. I’d bet on it.

I miss Vance Phillips

I RECEIVED THE FOLLOWING LETTER

IN RESPONSE TO MY STORY. IT IS SELF EXPLANATORY.

Dear Mike,

Dee just sent me a piece that was forwarded by Nancy...one you

had written regarding my cousin Vance Phillips. I enjoyed it immensely and could only think of the times Vance and I had cooked

up our on brand of mischief here in Pampa, Texas. It prompted me to write and tell you one other humorous story, one that

Vance could have probably had his stripes pulled, but one of those "insider" family-stories.

My dad was Fred Vanderburg and Vance

adored everything my dad was and stood for. Some of his favorite times were spent in the Panhandle on our farm and ranch.

I have several fond memories about Vance...like riding a horse and running a herd of cattle through a barbwire fence-- out

on wheat ground ( He thought he was Roy Rogers the second), or his suggestion that he could "kill" the boar pigs better than

my dad as they were being castrated, but this short story has to do with his ability as the pilot we loved.

Dad just happened to be putting out fertilizer in the field--

which up here is done by pulling an applicator with a tractor. Dad's hired hand, Callan George was a short distance away tending

to a chore, when out of nowhere came a sound from you know where...a sound way louder than the noise of the tractor. Of course

it was Vance...flying just above the tractor. As Callan later reported, he spotted my dad jumping out of the tractor and circling

it and the applicator two or three times trying to figure out where that dang noise had come from. . Of course Vance was completely

out of sight by the time dad had the tractor stopped. As only Vance would do he made another pass over Dad's tractor ending

it by cork-screwing up over the tractor and straight into the sky. Not too long later there was a telephone call from Vance,

someplace in Louisiana, which verified the culprit. Needless to say, the hogs went crazy and the rural neighborhood still

speaks of the day they thought the world had ended.

It was indeed a painful day for us all when we lost Vance. The only consolation in

it is we know he was doing what he loved. Once again, thank you for your wonderful story, and I hope I haven't bored you with

my sharing another "Vance Story.”

Sincerely,

Joy Rice

(Vance and Dee's first cousin)

BELOW IS AN EXCHANGE MADE BETWEEN DEE PHILLIPS AND I ABOUT SOMETHING THAT HAPPENED IN MY LIFE OCTOBER 30, 2010 AT A GATHERING

OF PILOTS IN AUSTIN, TEXAS. TO ME, IT WAS AN AMAZING EXPERIENCE.....MLM

| SHAMELESS WANNABE |

|

Dee, It has been a strange day. I am member of a flying fraternity called the Quiet Birdmen. They call themselves

an Ancient and Secret Organization, uh, so I cannot tell you much about it except that it started after the first world war,

and several famous people, like astronauts, and Lindberg have been members. You have to be invited in, and meet certain

qualifications. Today we met for lunch at Lago Vista airport west of Austin and on Lake Travis. I flew my RV-6A

over there to show it off. As I was standing in line to get my burger for lunch, there was a guy in front of me wearing

an F-100 T-shirt, announcing an organization of some type. Curious, I asked him if he flew them in VietNam, of course

thinking about Vance, and the guy replied yes, and I further learned he did his pilot training in 1957, and that little factoid

stopped me from asking the burning question in my mind, and the question was, did he ever run across Vance Phillips.

As we sat down to eat he was talking to the guy on his left, and it both turned out that they both were from Walla Walla,

Washington. The guy on his left then mentioned something about the other guy the two of them had run across in Vietnam

that also was from Walla Walla, and he had been a FAC, and the FAC driver had helped the the guy next to me, a 100 driver,

in a SAR mission in Cambodia. The third guy said, and what was that Hun driver’s name, the one who punched

out? The answer was Vance Phillips! I spit my beans out and said, “What did you say?” “You

just mentioned someone’s name, what was it?’……Again he replied, “Vance Phillips.”

I quickly told

him my story of knowing Vance, and he was absolutely astonished. He stood up and told the story to the whole bunch about

the SAR and told them he was sitting next to a guy who personally knew his lead the day the lead got the whole belly knocked

off his F-100. Below is the story as he published it on the web. He does not mention Vance’s name, but Vance

was leading the two-ship formation that day on an air-strike to knock out two camo boats on the river that had been identified

as bad guys. I was just floored. Michael Lewis Moore.

HOW TO ACQUIRE CAMBODIAN PILOT WINGS

by

Lester G. Frazier

This is the story of a rather unusual combat mission.

The fact that I acquired a set of Cambodian Pilot Wings as a result of the mission is ancillary, but it's a good story and

a true one.

In 1970, I was posted to Phan Rang Air Base, Republic of Vietnam, flying F-100Ds. It was my second combat

assignment to Phan Rang in the F-100 and my third In-Country tour, having flown the L-19 out of Phouc Long Province back in

1962-63. We had an Alert Pad at Phan Rang with eight Huns uploaded, in flights of two, on five-minute alert. The object of

the alert pad was to provide immediate air cover for friendlies needing it or for high priority targets that could pop-up

and need prompt attention.

My first tour on the alert pad was as the number two man in a flight of two. Although I

probably had as much combat time as my young leader had total time, the regulations stated that you couldn't lead off the

pad until you followed at least once. I didn't have any problem with that as my leader, although a relatively inexperienced

lieutenant had a good set of hands and was aggressively disciplined. His name was Vance Phillips.

We reported

to the pad early in the morning, relieving the night alert crew, and preflighted our airplanes, uploaded with four 500-pound

Mk.82 high-drag snakeyes.

The high-drag snakeye had a steel umbrella that opened on release, slowing its speed considerably.

This did two things: it allowed the pilot to get in close to the target and allowed him to egress the fragmentation envelope

before the bomb detonated. Our birds also had all four 20 millimeter cannons loaded with a high-explosive incendiary and armor-piercing

incendiary mix.

We sat around all day and finally received a scramble order late in the afternoon. We were airborne

within three minutes and copied target information as we climbed out. All we were told was that our target was boat traffic

on the Mekong River in Cambodia. Nothing to write home about.

We usually worked with a Forward Air Controller (FAC),

a pilot of a slow moving aircraft who spotted targets and controlled the fighters attacking the target. When we were within

radio range, my leader contacted the FAC, Rustic 08, and told him who we were and what ordnance we carried. Zero Eight told

us that our targets were two 100 foot camouflaged ships, nestled in the trees, up against the western bank of the south flowing

Mekong. He included other information such as the position of the nearest friendlies (none around), target elevation, altimeter

setting and recommended attack heading, which was from east to west. He correctly determined that it was impossible to visually

acquire the targets on any other heading. However, an east-west run-in would have us attacking directly into the sun in the

late afternoon of a high humidity day with associated haze. Adding to the attack problems was a 50% cloud cover at the altitude

best for commencing the attack. Zero Eight also recommended that we circle to the north after each attack, as a huge mangrove

swamp north of the target would preclude bad guy harassment as we set up for the next attack.

At one point my leader

asked Zero Eight how he knew the ships were unfriendly. He said that he had a Cambodian pilot in the back seat of his OV-10

Bronco and that the Cambodian government had declared the ships unfriendly. We were all jaded enough to realize that the target

could be a business rival of the local commander, but ours was not to reason why...

When Zero Eight said he had a

Cambodian in the back chair, I jumped on the radio and asked if he could get me a set of Cambodian pilot wings since I collected

military pilot wings.

In a fighter flight, protocol dictated that everybody in the flight keep his mouth shut, except

for leader, but, I wasn't about to miss a chance to acquire a set. After some discussion with the Cambodian, Zero Eight said

that he would take care of my request if I called him that night. I made sure that they understood I wanted pilot wings and

not hat brass, air force insignia, stickpins or whatever, got his phone number and we proceeded with the mission.

We

set up our switches for bomb-single, took spacing and Zero Eight rolled in and marked the ships with a white phosphorus smoke

rocket. Zero Eight moved away from the target and told leader he had him in sight and he was cleared to drop on his smoke.

All total, we probably made seven or eight passes, dropping all of our bombs. We damaged the ships but did not sink them,

and I could truthfully say that I never saw the targets. But, one of our bombs opened up the jungle just west of the ships,

exposing an oil storage depot. Clearly now, these were the bad guys.

I saw Rustic 08 pull straight up, hammerhead

his Bronco around into a ninety degree dive, and drill a rocket straight into the middle of the depot. The depot started to

explode and burn and Zero Eight cleared us in for gun attacks. Almost as an afterthought, he said, "move it around, the guns

are up." What he meant was that he had taken ground fire, and suggested that we keep our flight paths unpredictable. We made

several passes, adding to the general morass, when leader attacked the depot amidst tracer fire from south of the target.

I told him he was taking fire, and went back to pulling my airplane around for another pass when leader transmitted, "OH SHIT,

I'VE JUST HIT THE TREES!" I aborted my pass and asked him his position. He said he was turning north and losing hydraulics.

Rustic Zero Eight transmitted that he had him in sight and was taking up a chase position. To do so, he had to fly across

the guns, which shot at, but missed him. I remembered thinking what a gutsy FAC, to have flown across hostile guns to assist

a Hun driver he had never met and couldn't possibly catch. A few seconds later leader transmitted, "My hydraulics are gone;

I'm stepping out." I still couldn't see him and asked his position again. He said he was north of the target, headed southeast.

I knew he was over the mangrove swamp and if he jumped out, he'd spend the night there, if he survived the landing. I asked

him if the bird was still flying, and he said that it was, but his control stick was frozen. I told him to stay with the bird

as long as it was flying.

Zero Eight gave him distance and heading to Bien Hoa Air Base, the nearest suitable landing

field. About that time, I spotted Zero Eight and eyeballed a line-of-sight directly ahead of him. About 10 miles ahead and

high was my leader. He was just a tiny speck in, and amongst, the clouds. Without taking my eyes from him, I slammed in the

afterburner and closed rapidly. I came aboard at about Warp Nine, threw out the speed brakes and performed an energy-losing

maneuver (called a high-speed barrel roll) around leader. I matched his 240 knots, which was over 100 knots slower than his

best climb speed. But leader, with no airspeed indicator, had no idea what his air speed was.

As I eased onto his

right wing, I was shocked to see the entire bottom section of the fuselage missing from the main wing's trailing edge to the

tail. I could see the entire engine and various accessories attached to it. F-100 Pratt & Whitney J-57 engines were shoulder

mounted and, for that reason, it was still positioned correctly within the fuselage. The rest of the airplane was garbage:

the wings and horizontal stabilizer were torn up, the nose was bent and the pitot tube (airspeed measuring device) was missing

and tree branches driven vertically into the underside. I had seen other F-100's that had hit trees and returned to base.

They all had foliage buried in the wings leading edge. For that reason, I hadn't thought my leader had hit the trees. Rather,

it looked like something had blown up underneath him and ripped his airplane apart. Leader told me he had some control. By

varying his engine power, he could raise or lower his nose sluggishly, and the rudders still worked. About eighteen years

later, Captain Al Haynes of United Airlines would face a similar dilemma, as he and his crew heroically guided his passenger

filled DC-10, onto the runway at Sioux City, Iowa.

With the sun setting, we dived, zoomed and skidded our way through

the clouds 147 miles to the South China Sea. Leader had decided that he did not want to eject over the jungle if he was able

to make it to water. The entire time, Rustic 08 had given us the best information he had on our position, safe bail out areas

and weather data. I had called up SAR (Search and Rescue) and we managed to make one large circle, while the Jolly Green positioned

himself below us, just off the coast of Vietnam, near Vung Tau. Leader successfully ejected from 12,000 feet, and the chopper

picked him up immediately and took him to Bien Hoa. Needing fuel, I landed at Bien Hoa right behind Rustic 08. The ground

crew took me to his operations, where I thanked him for his superb support, and gave him my address for the wings (which arrived

in a few days). I then went to the hospital and checked on my leader, who was uninjured.

A couple of weeks later,

the Phan Rang newssheet carried an article about the rescue. As always, they listed name, rank, age and hometown of the article

participants. The information about me was correct but no hometown was listed. This didn't surprise me because I wasn't interviewed

for the article. But, the hometown of the rescue pilot was listed: Walla Walla, Washington, which is my hometown. As Chief

of the Command Post, I had extensive communications available to me, so I located the pilot who was now flying out of Danang,

and thanked him for his efforts. I asked him if he really was from Walla Walla. He said yes, and named an uncle, Lester Keen,

who still lived there. Lester Keen, of course, was my dad's best friend and the person for whom I am named.

Below is a narrative written by Vance about his second time he had to punch out of another

damaged airplane.

Lt.

James Vance Phillips

Aircraft

/Accident/Combat Loss Narrative

On 10th

February 1970 Major Burney and myself were returning from the target having

expended soft loads on suspected enemy positions. At about 1415, one hour and

ten minutes after

takeoff, I noticed vibrations throughout the aircraft. These, I thought, or

hoped, might be coming

from the tail hook, so I asked lead to take a look at the underside of my

plane.

Having

done so, he reported no abnormal appearance of the tail hook which left only

the engine as the source. By this time

the vibrations had increased to the point of shaking the aircraft.

The

shaking appeared to be a long series of staccato compressor stalls (the engine

was failing) that steadily increased in proportions. This all occurred at between

91 and 94

percent RPM,

Our

position at this time was 40 miles out from channel 75 and turning to intercept

the 225 degree radial. Thinking to make

a straight in approach from 17,500 MSL, I pulled the power back to 87

percent. The shaking stopped momentarily

(approximately 5 to 10 seconds) and then 3 extremely large compressor stalls in

rapid succession. The engine flamed out

after the last of the three stalls.

We had,

at this point, turned toward feet wet (over water) and I began to go through

the emergency procedures for air start. All attempts and re-attempts failed to

show any indication of a restart.

In the

meantime,

I had begun to clean up the cockpit for a controlled bail-out over the

water. I took out my water bottle from

the G-suit pocket and slid it along with my checklist and brain container under

the rudder pedals. The latter I

concluded to be non –essential and the former dead weight to be avoided in the

lower extremities due to the flailing of the legs that might be caused.

During

this same time period, I tried to assess the situation, deciding the best bail

out altitude and airspeed. Dive angle

did not enter my mind as I had associated the upward vector to be related to a

need for increase in altitude prior to ejection. (I recommend this procedure

be stressed to

other pilots.)

At 5500

feet MSL (above sea level) and with 3 degrees nose low, at 245 knots, I raised

the handles and the canopy left the airplane.

Thinking somebody must hate me, I pulled the triggers and felt the

extreme acceleration forces and wind blast.

The next thing I knew I was coming out of the seat and immediately the

chute opened.

My head

was down (about 30 degrees) when the chute popped and my helmet came off. From

the loss of the helmet I received the

only scratches of the incident about my face and cheeks.

I “cut

four” the first thing, deployed the seat kit and opened one L Pulls, deciding

to save the other until I was in the water.

I did not open the J-! releases for fear of separating from the chute

and possibly puncturing my good LPU on impact.

After

accomplishing this, I took out my URT-64 (HAND HELD RADIO) and talked to Major

Burney to relay my good fortune at a good chute and successful ejection in

general.

We

talked for a while and continued, of course, to descend. As I neared the water,

I stowed the radio and

prepared to enter the water. I turned in

the chute so I was facing the wind and hit the water shortly thereafter.

Not

having opened the J-1’s earlier, I was dragged beneath the water about 10-15

feet by a reported 125 knot wind before I could get the canopy detached.

I

opened the other LPU (LIFE PRESERVER UNIT) and got into the life raft butt first

from the

back of the raft. I got in on the first

try with no problem whatsoever. After

getting settled and comfortable in the raft, I again took out the URT-64 and

spoke to lead, who was running low on fuel by this time. He told me that there

was another flight of

F100’s on the way to take over the rescap duties. (rescue combat air patrol) Then

I opened the survival seat pack and took

out the flare and sea marker dye and toyed with the idea of going fishing but

decided against it due to the near presence of Pedro. (Note from Mike: Pedro was the rescue helicopter) He

was not even airborne yet.

I

rummaged through the seat pack but found nothing else of use at the time, so I

set out the sea marker dye and readied the flare and settled back for what I

hope would be a short wait for a rescue chopper.

When

Pedro came onto the scene, he had a little difficulty in locating me since an

army helicopter had been orbiting for near to 10 minutes and gave him vectors

to my position.

A horse

collar was lowered to me and I got into it without difficulty, however the

L.P.U.’s were somewhat in the way while being raised on the hoist and I had to

hold on tighter than otherwise have been required had they been deflated.

The

return trip in Pedro was uncomfortable due to my damp state and the drafty

machine caused a chill to set in.

As far

as my recommendations, I would like ask that angle of attack on ejection,

unfastening the L-1 release covers and

possibly opening both L.P.U’s be stressed to other pilots. I am not sure,

even now, about the L.P.U.

procedure. The procedure I used has its

merits but so would the water entry use of both. I would like to know the official

recommendations on this.

James

V. Phillips L. USAF

The

above typewritten narrative was taken from a hand-written document sent to me

by Vance’s widow, Nancy Hinds Phillips.

I thank her from deep down because it came to me because she knew I was

interested and cared, not because I asked her for it. In fact, I have searched

the web relentlessly

over the years for this second ejection event of Vance’s without success. I

don’t know if it was the nature of the

mission flown or what, but I could find no hint of it until Nancy sent this.

|

| Vance very wet but wrapped in a dry blanket after pick up by the rescue copter |

SCROLL UP FOR MENU

|